Why Aussie house prices hit a new high (and NZ’s housing market is in a slump)

Australia has enjoyed 18 solid months of price growth.

June was a bad month for the New Zealand housing market. The nationwide median sale price was down 1.3% year-on-year, while house sales were down 25.6% over the same period.

In fact, according to data from the Real Estate Institute of New Zealand, it was the worst sales count for a June month since 2008 (and in Auckland, it was the worst June since records began).

Across the ditch, house prices were on the rise.

Data from listings website realestate.com.au showed a 6.55% annual lift in Australia’s median property value. The site’s senior economist said prices for June were a new peak and followed 18 consecutive months of growth.

So why is Australia’s housing market glistening and New Zealand’s gloomy?

The answer seems to be supply and demand. In New Zealand, the market was flooded with listings at the start of the year, turning a nascent seller’s market into a full-blown buyer’s market. In Australia, stock levels have grown but not enough to meet demand, with realestate.com.au citing strong population growth, a tight rental market and a “chronic shortage of housing being exacerbated by a lack of new construction” as contributing factors.

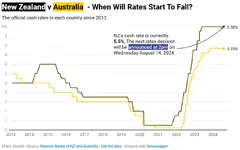

House prices in Australia and New Zealand were on a similar trajectory immediately after Covid hit, when low interest rates fuelled a buying frenzy and FOMO (fear of missing out) reigned supreme.

Both countries also suffered a housing market slump as central banks raised interest rates hard and fast in response to rising inflation. But the countries’ paths diverged at the start of the year.

Experts told OneRoof that confidence in the Australian economy has made a difference. “I’m not seeing a lot of Australian news about government cutbacks or public sector cutbacks,” said Wayne Shum, senior research analyst at OneRoof’s data partner, Valocity.

Australia has also continued to experience strong net migration, whereas new arrivals to New Zealand have waned in recent months.

Matt Grudnoff, senior economist for independent thinktank The Australia Institute, based in Canberra, said unemployment in Australia was still low but pointed to another key difference as to why Australian house prices were growing – active investors fuelled by tax breaks.

“What is driving Australia’s housing market is a combination of a number of tax concessions, which make investing in housing quite lucrative.”

Australia has a capital gains tax and a capital gains tax discount. While owner-occupiers were not liable for the tax, investors were but they got a discount, which meant if they bought a house for $500,000 and sold it for $700,000 the tax office ignored half the gain.

“Of that $200,000 gain you only get taxed on $100,000. The other $100,000 is entirely tax-free.”

The capital gains tax discount applied to all assets, not just housing, but had been particularly used for housing, Grudnoff said. “You’ve got to own the asset for more than 12 months but when it comes to housing obviously that’s pretty common,” he said.

“What we’re seeing in Australia is house prices go up quite dramatically and as they’ve gone up that’s attracted more and more people who are investing in housing, because rather than investing in it to make the best rental return, if you like, they are actually mostly interested in the price going up, because that’s where you make most of the gain.”

That was combined with a “real drop off over decades” in investment in public housing by Australian governments, which had also driven the Australian housing market because it effectively meant less housing coming onto the market.

“In Australia, housing developers tend to release housing bit by bit when it’s most profitable to do so, whereas if you go back several decades when the Government was building at a steady constant rate that was just adding to supply in the market which was effectively putting a limit on how quickly house prices could rise, and, also, more importantly, how quickly rents could rise.”

A lot of the investors buying already owned a number of properties and came with capital so found it easier to borrow money. “They’re quite good at basically out-bidding first-home buyers or owner-occupiers and that’s basically forcing them out of the market,” Grudnoff said.

While New Zealand was seeing steady reports of Kiwis quitting New Zealand for Australia, they would be casualties of a tough housing market there, too, Grudnoff said, and the outcry from the younger generation being locked out of the market was rising along with house prices, and rents.

“We see quite an age differentiation between who’s being hit by the latest spike in inflation and that’s actually a housing split, so we’ve seen rents rise dramatically and people with large mortgages, usually younger people who have just bought into the market, have also been hit hard.”

Older people had not been hit as hard and were continuing to invest – and Grudnoff was not pointing the finger at baby boomers when he said older people. “I’m Generation X. We like blaming the boomers because it avoids us but to be honest the boomers are mostly retiring so increasingly it’s people in their late 40s, 50s and 60s.”

Grudnoff was not expecting Australia’s housing market to follow New Zealand’s into another slump. “I think there's a general feeling that Australian house prices don’t go down a lot,” he said.

“It will be interesting to see what happens but even with interest rates probably kind of at their peak at the moment, we’re still seeing house prices increase.”

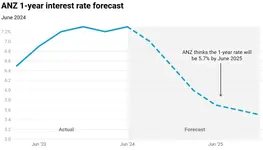

Asked what would happen when Australia’s Reserve Bank cut the country’s cash rate, Grudnoff said he assumed house prices would begin to rise more rapidly because that was what usually happened.

View attachment 8332

View attachment 8333

None of the major political parties had put up any real solutions: “They’ve been mostly piecemeal. They’ve been either tiny or they’ve actually been things in the past that have made housing affordability worse,” he said.

Vanessa Rader, head of research for Ray White, said there was a mismatch in Australia between limited new supply due to high cost of construction and the difficult labour market, with continued growth in population resulting in record high rents, low vacancies and median prices growing across each state.

“Limited listings fueling FOMO despite high interest rates as buyers look to secure accommodation as despite increased cost of living, low unemployment is keeping sentiment strong.”

She said one of the main differences between the two countries was the level of available stock, saying with listing numbers high across New Zealand rents had softened and buyers had choice, which allowed them to negotiate prices down. “Sentiment is down across New Zealand given high inflation and interest rates, also an uncertain labour market, making decision-making difficult for would-be buyers.”

A reduction in the cost of finance would do much to stimulate activity again, she said.

She saw the change in movement in interest rates as an influencing factor in the divergence of the trajectories. New Zealand moved first in increasing interest rates and further rate rises knocked market confidence. “This really stopped activity, with buyers opting for a wait-and-see approach to their next decision.”

But the next interest rate move for New Zealand was likely to be downward and that would improve confidence in the economy and sentiment would shift resulting in an increase in activity which would have a positive impact on prices.

In New Zealand, CoreLogic chief economist Kelvin Davidson said the markets in each country did have similarities in that while mortgage rate levels might be different they were still high.

“Housing affordability is still stretched here, and it’s still stretched there,” he said.

Australia might be on the cusp of a downturn, too. “Who knows what might happen next month?”

Davidson, too, spoke of labour market factors with the Australian labour market holding up but New Zealand’s weakening one high in the public perception.

“We’re seeing some job losses; we’re seeing job security go down. Even if you haven’t lost your job you’re probably still not feeling as secure as you once were, so I think that is where you start to see a bit of a difference.”

Shum also said mindset was an important factor in the housing market: “Property is all about confidence. If you think we’re not bouncing back anytime soon that spreads around.”

Australia has enjoyed 18 solid months of price growth.

www.oneroof.co.nz

Interesting that we are repeatedly told that a CGT would keep down house values in NZ, yet Australia is experiencing huge growth in their values despite having one while NZ's house values over the entire country are still in decline. So much for the new government in NZ being in the pocket of property owners (especially landlords).... perhaps if they were, they would introduce a CGT here so NZ landlords can experience that sort of growth too!!!

www.rnz.co.nz

www.rnz.co.nz